Ellen Atkins on Charlie Atkins, 1928-2013

The Many Voices of Peace Studies: Celebrating 50 Years

Ellen Atkins on Charlie Atkins, 1928-2013

Ellen Atkins, wife of Charlie Atkins, says her husband was a lovely man, and a lovely child.

Charlie, who was a prominent businessman, peace activist, co-founder of the Peace Studies program, as well as a major donor to Peace Studies, was generous at heart, even though he experienced many hardships in life.

The First Tragedy

Among the first was on Christmas Day 1947. Charlie, 19, and his three brothers, parents, and another young passenger were hit by a drunk driver while heading to family who lived in Tennessee. His dad died at the scene. His mother passed later at the hospital.

“His mother said she was fine,” Ellen says. “They took her up and put her in a hospital room and she talked to him again and said, ‘I’m fine.’ And she was dying. She had her chest crushed, and oh my gosh, she was just such a sweetheart. She didn’t want the kids to think she was dying.

“It was tragic. Charlie had no home. So, he lived with his older brothers for a while.”

At the time of the accident, Charlie was going to Westminster College in Fulton. A year after the accident, he transferred to MU where he received a BA in business and an MA in extension education. He also took a lot of sociology courses and an ROTC emphasis.

“He was kind of homesick in Fulton,” says Ellen. “He liked it much better when he came here (to Columbia). He took ROTC because he thought that’s what a good American would do at that point in his life. He still thought the military was great.”

And Yet Another

Another tragedy struck after he graduated and became a first lieutenant in the Army and shipped to Korea (1951). During that time, he spent six months on the front lines as an artillery officer, where he was severely injured by shrapnel.

Since he was a substitute artillery officer, he didn’t go in as a group, and didn’t have the comradery of being with a troop, Ellen says.

“He was completely an outsider. It’s kind of a hard way to live when different units would get together and see their buddies from 10 to 20 years ago. He didn’t have anything like that.”

Ellen says when he was injured, he had to be carried down from a mountain.

“The medic pulled out cellophane from his cigarette pack and put it over Charlie’s lung. And that’s why he lived. It wasn't like two blocks from the car to the hospital. In later years, while undergoing a medical procedure, he had a test to see if he had any metal in him, and he said, ‘Oh, I have shrapnel everywhere.’”

He ended up spending six months on a Dutch hospital ship. In 1953, he was shipped home where he recovered and began his career working for the family store: Stovall’s Clothing. He went on to open his own store in Kennett, Missouri, in 1955.

Life After War

“When Charlie came back from the service, he might not have been furious with the Army, yet he realized they taught him to be a killer,” says Ellen. “And that had to make you really messed up.”

As a result, he suffered from PTSD. And he thought about war, what it was, how much people suffered.

“And he’d say to me, ‘I called them the enemy and for that reason I thought I had the right to kill them. But you know, those people were just like me. They are human beings.’ And that was really hard on him.

“I told someone what he said, and they said, ‘Look at how much he accomplished regardless!’ You know, he wasn’t a broken person.

“But by the time he got home, he wasn’t feeling the best. And he didn’t realize until he got home how much he didn’t like the military. He thought ‘This is America and that’s the way it is.’ It wasn’t until he saw the Vietnam War on TV that he realized how you take just a very plain person, put them in the Army, teach them to kill. You change them.”

Charlie was awarded the Purple Heart and Silver Star for valor.

The Early Years

Charlie grew up in a religious home, which influenced him heavily in his younger years. He was raised Methodist, and he believed their teachings and embraced the experience.

“He thought he could just hold God’s hand. He believed that. He was, I guess, around 10. And then as he grew older, he did a lot of reading. Reading was one of his passions.”

His father was also a strict man, and he and his brothers often got in trouble. Sometimes the punishment was to go into the backyard and dig a large hole.

“And when he did, he’d have Charlie throw the dirt back in. He just knew they needed something to do.

“Also, his dad would take him to the store sometimes, and when he couldn’t find him when it was time to go home, the alterations lady said, ‘oh, he’s asleep under the sewing machine.’ He must have been pretty young.’”

But Charlie’s family also gave him the opportunity to explore sports.

“And in Poplar Bluff where he went to high school, they’ve got pictures of him with all his awards in a case,” Ellen says. “You know they do that with special athletes. Football was his main sport. But the way he told the story, he thought he was really a hotshot football player. That is until the line graduated. He said he just got killed when those big boys graduated. So, he made a joke out of it. He loved also to watch basketball and football.

“He had accolades from high school, quite a few, and was on the National Honor Society and got the highest level in Boy Scouts – The Eagle Scout.”

Branching Out

As Charlie got older, he took a more informal approach to religion and life in general – becoming a member of the Unitarian-Universal Church of Columbia.

“The religion he introduced me to was being a humanitarian,” Ellen says. “We have every kind of religions, people with different kinds of religions, that come into our church.”

He also was a voracious reader, absorbing the teachings of Gandhi, Einstein, and Thoreau.

“He read mostly nonfiction, or political, or philosophical,” Ellen says. “He scribbled all over the books, just like I still do. And he put question marks or indicated parts he liked. And I love to reread the books he’s read.”

Expanding Business

Meanwhile, his business grew and prospered. He became general manager of seven stores. “Charlie loved to work hard,” Ellen says. “I think one of the things I respected most about him was how he was so used to being interrupted. If he was interrupted, he would immediately turn to the interruption, solve that, then go back to what he was doing.

“And with any job he did, he was very conscientious. Nothing ever slipped by him, and he kept marvelous notes on things. Sometimes I even find them tucked in a book. And I just love it.”

Founder of Many Things Peace

In 1971, Charlie became co-founder of MU’s Peace Studies Program – making it a structured program with funding. He also was president (1992) of the Veterans for Peace Mid-Missouri Chapter, which was later named Charles Atkins Chapter of Veterans for Peace. He donated heavily to the peace movement, and his financial support was key in its success.

“Charlie was just so disappointed in his war experience when he realized what war did to people,” Ellen says. “And he wanted classes taught at the university that could teach about peace instead of war.

“There was already a cadre of people who wanted to do that, but they didn’t have any money. He had inherited some money from his father and had at least one standing store. Charlie said, ‘Oh, I’ll throw in some money,’ and he threw in $25,000. They said it kickstarted them.

“They weren’t teaching very many courses because nobody was paying the salary of the people. And he wanted to have at least one class where others could teach Peace Studies. The reason he did it, was that he just wanted to show people that there is an alternative to war. You don’t have to say, ‘We’re in an argument, so we’re going to war.’”

Charlie not only donated for one class, but also for interdisciplinary classes such as English, sociology, history and others so more professors could teach a Peace Studies course. They would teach it within their majors, but emphasized peace in parts of it, expanding the movement across campus.

Charlie also taught peace studies classes in elementary schools, and participated in protests. Ellen says many of his awards for his work still reside with his children and grandkids.

“He was also so loving of everyone. At least in the last years of his life. And he loved to laugh and made people laugh. I admire his dedication to Peace Studies, and I admire his loving dedication to me.

“I just admired all the things that he was into – you know religion and reading and philosophy and his heroes, and the fact that he went through war and survived. And instead of being angry, well he did have anger with his PTSD, but let me tell you he handled it really really well.

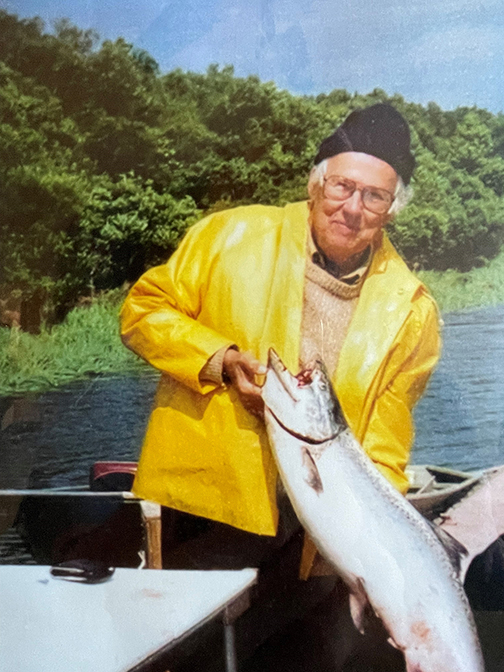

“When I first met him, he told me I was the reason he wanted to live, because he thought about killing himself,” Ellen says. “And then later on, he told everybody that he thought about fishing, that he wanted to live for fishing. And when he said that, I thought ‘Hey, you told me you wanted to live for me.’ So, yes, he was human. He was a hero though. I’m so lucky he wanted to marry me.”